Angry Incidents Display Depth of a Nation’s Wounds : Chile: The lingering tensions enlarge President Aylwin’s task of helping scars to heal.

- Share via

SANTIAGO, Chile — As President Patricio Aylwin proclaimed a new democratic dawn in Chile in his first speech Sunday from the front of the presidential palace, bands of angry leftist youths were hurling soft-drink bottles at police tear-gas vans behind the palace.

It felt for a moment as if the dictatorship of the last 16 years were still intact, as if Aylwin had never wrested the presidency from Gen. Augusto Pinochet at the ballot box rather than at the barricades.

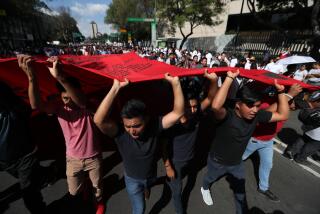

The skirmishing, which left 79 police officers and 118 civilians wounded, was one of several reminders during Sunday’s otherwise joyous inauguration of just how deep the wounds run in Chile. A series of incidents underscored the magnitude of the task facing Aylwin in reaching his oft-avowed goal of helping the scars to fade:

Relatives of those who were killed during Pinochet’s reign threw tomatoes at Pinochet as he arrived at the Congress to surrender the presidency. Inside the chamber, during the ceremony itself, some shouted “Murderer!”

Pinochet supporters taunted Vice President Dan Quayle, calling him “son of a whore” and other insults, when he visited Pinochet’s home before the ceremony, and small pro-Pinochet groups disrupted caravans of pro-Aylwin celebrators in well-to-do neighborhoods Sunday night.

Finally, the street violence broke out during the public celebration for Aylwin at La Moneda, the presidential palace. It was no different from the many clashes between pro-democracy demonstrators and the police throughout Pinochet’s rule, except that this time the helmet-less police showed far more restraint. They withdrew when the crowds overran metal fences and only resorted to the tear gas and batons when a barrage of debris rained down on them.

Ten policemen were seriously hurt, and 59 remained hospitalized Monday. Twenty-eight civilians were badly hurt, the police said.

Aylwin, a 71-year-old veteran politician and master negotiator, is aware of the lingering tensions. In his first address, he said: “This creature that is being born, this freedom that we are reconquering--we must care for it. And we are going to care for it to the extent that we know how to respect each other, and the extent to which we never again become enemies of other Chileans.”

While Chile’s vocal extremes unleashed their anger, there were also signs of the kind of reconciliation and compromise that infused the movement to restore democratic rule, and the support given to that process by most Chileans, those who never attend any kind of demonstration.

Aylwin stood in an aging black Ford Galaxie convertible Monday morning for a motorcade through the capital to the national cathedral for an ecumenical service attended by religious leaders from many faiths. Along the route, office workers leaned out windows and roared their support. Passers-by on their way to work, some smiling through their tears, applauded until their hands hurt.

Aylwin, the elected politician who ousted the army general, passed through cordons of immaculate troops and uniformed police, saluting him as military bands played patriotic songs.

When a band finished the national anthem after Aylwin entered the cathedral, the people pushing against the crowd-control fence in the Plaza de Armas spontaneously continued to sing it without accompaniment and with fervor.

Even with such support, the new government, built from 17 parties whose only common ground was opposition to military rule, now needs to confront the daily tasks of governing. It inherits some enviable growth statistics from Pinochet: inflation of 21% last year, lower than the monthly rate in most nearby countries, and unprecedented growth of 10%.

But prices for copper, Chile’s largest source of export revenue, are declining. The overheated growth has raised fears of higher inflation. The government faces pent-up demands for a more equal sharing of Chile’s new-found wealth just when it needs to reassure foreign investors that Chile remains a safe place to do business.

“This is a deeply divided country, and the task of the next government in rebuilding democracy will be to bring about understanding between Chileans,” Aylwin said recently.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.