Artists’ Work Spans U.S., Soviet, Mexican Borders : Art: Four mural creators brought together by the Soviet arts festival work under the spirit of a fifth and legendary influence.

- Share via

In a Balboa Park cultural center gallery-turned-studio, four artists apply paint to canvas with the spirit of a fifth artist in their midst.

Nikolai Ignatov and Temo Gotzadze of the Soviet republic of Georgia, Miguel Najera of Tijuana and Victor Ochoa of San Diego are putting together “Fronteras--Soviet/U.S./Mexico,” a project of the Soviet arts festival.

All four artists are known for monumental work--murals that reflect their respective, diverse cultures. But aside from being artists working in a common genre, they make an unlikely quartet.

They have, however, one other common tie: legendary Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros.

It’s no surprise that Najera and Ochoa would be linked to the late Siqueiros. Ochoa is an integral figure in the Chicano art movement, which found inspiration in the work of the great Mexican muralist and his contemporaries Diego Rivera and Jose Orozco. Najera studied at the Siqueiros institute in Cuernavaca, and his work shows obvious stylistic influences.

But Ignatov and Gotzadze also have ties to Siqueiros. Gotzadze has traveled throughout Mexico and seen the greatest works of the master. And Siqueiros, while visiting Georgia in the early 1970s, paid a visit to Ignatov’s studio.

Four languages are being spoken in the room--English, Spanish, Russian and Georgian. An interpreter is provided for press interviews, but otherwise the artists are on their own. Ignatov speaks a little English, Gotzadze almost none. Najera and Ochoa have picked up a few Russian and Georgian words. There is little verbal communication.

But the spirit of a fifth language is in the air and on the walls--the universal language of art.

Pepper Grove is on Park Boulevard, in the middle of Balboa Park. At one end of the grove, across the street from the Navy Hospital, are two water tanks. One is no longer in use and is scheduled for demolition. The other is a little harder to dismiss.

A colorful mural adorns the circular wall of the tank that houses the Centro Cultural de la Raza. The mural depicts a microcosm of Chicano culture--indigenous, Spanish and Mexican imagery with a vibrancy heightened by the curved surface.

Step inside and shapes change. Now you are in a squared circle. A series of high, flat walls form right angles, and in four distinct areas, the artists are at work.

Each was provided five 6-foot-by-6-foot panels.

Ochoa, who gave one panel to Najera, is at work on an abstract piece that will incorporate elements from the work of his colleagues. Najera’s 12-foot-by-18-foot piece is a swirling, tempestuous study of the harrowing border crossing made by many of his compatriots.

On this day, Ignatov is trying to decide whether to compose his canvases in a cross or in an upside-down “T.” His disparate images somehow look right together. Adam and Eve flank a tree, fallen apples at their feet. Above them, on the highest canvas, is a stone--an image that seems a signature for “Koka.” The final canvases will include figures to illustrate the work’s theme: “He who seeks shall find.”

Gotzadze has formed a cross with his canvases, which depict a landscape of fantasy. A woman’s face is painted into the side of a mountain, upon which sits a house. A winged horse has a cross on its head. At the top, ghostly figures float among the clouds. At the bottom, a naked figure, perhaps a child, tumbles into a gaping hole in the ground. The last panel features a voluptuous nude woman, lying across a field. Suspended in the sky above her is what seems to be Gotzadze’s signature image--an apple.

And there is a clue as to what distinguishes the two Georgians. In Ignatov’s darker work, the fallen apples in a sparse, gray field represent the loss of innocence in Eden. In Gotzadze’s fanciful, romantic vision, the apple hasn’t fallen and Eden is still attainable.

This project was originally designed as a collaboration.

The artists were to jointly produce a large, public mural, the type of work for which they are all best known. But there was some difficulty addressing the theme of borders. Some people associated with the project thought the piece should be political in nature, but others didn’t want to overtly address an issue that is so sensitive in both the U.S.-Mexican border area and in Soviet Georgia, where a passionate separatist movement spawned several fatalities at a protest earlier this year. There was worry of disrupting this festival, which has seemed a diplomatic love fest but which has also seen some underlying tension between Georgians and Russians.

So the project is less a collaboration than a temporary cooperative. The artists help each other move scaffolding around the room. They nod approvingly at each other’s work. They did jointly produce one large canvas, partitioned into four triangular sections. In the top section, floating in the sky, surrounded by sea gulls, Gotzadze has painted an apple.

“The importance of this project lies in the historical, political, social and artistic parallels between Chicanos, Mexicanos and these Georgians in particular,” says Patricio Chavez, the centro’s curator and manager of the project.

“The concept of borders means something very different in Georgia than it does here between the U.S. and Mexico. Theirs is a border that goes beyond a fence and economic or racial differences.”

Chavez’s comments call to mind the adage “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States.” Substitute Georgia for Mexico and Russia for the United States, and you understand the Georgian dilemma.

Here, the border acts as a sieve for various influences. There, the Georgians wish the border would act as a blockade.

It’s a delicate topic. When asked about the situation in his homeland, a glum Ignatov lowers his head and simply mutters, “It’s very difficult.”

Although the Georgian separatist movement is a touchy issue, the artists find some consolation in the new spirit coming from Moscow. When the subject is art and the changes under Gorbachev’s rule, both artists are effusive.

“My first fresco, in 1962, took a year to complete, and it was whitewashed,” said Ignatov. “At that time, the powers considered it politically unacceptable. Now I could do exactly the same work without any problem.

“The mere fact that we are here talking to you is proof of the change--the fact that we can work here with our colleagues and express our own freedom.”

“The political situation has given the opportunity to every artist to express themselves freely,” added Gotzadze.

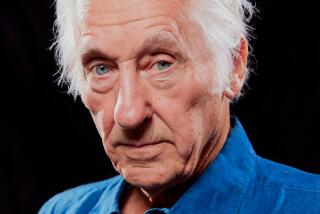

It’s a welcome change for these artists, who hold important posts in Georgia. Ignatov is a professor at the Georgia Academy of Art. He has exhibited throughout the Soviet Union and abroad--he has an upcoming exhibit in West Berlin--and also designs sets for ballet, opera, film and the stage.

Gotzadze is director of Georgia’s Museum of Modern Art. He also has exhibited widely and is preparing for a spring show in Chicago. He is secretary of the Artists Union of Georgia and a board member of the Artists Union of the Soviet Union.

They are both thoroughly enjoying their time here, they say, and although the collaboration didn’t occur as planned, they are still enthusiastic about the proceedings.

“When you work with others on a fresco, the most important goal is to exchange ideas, attitudes and feelings,” said Ignatov. “When you exchange ideas about a work, then try to reflect those discussions in the work, that’s the most an artist can desire.”

“But it’s not enough to achieve just that,” chimed in Gotzadze. “From this meeting, I expect the results will be continued and that we can begin an exchange for young art students. We shouldn’t stop at this present level. Otherwise, a one-time action is not important.”

The artists’ work in progress can be seen at the Centro Cultural de la Raza, 2004 Park Blvd., Wednesday through Sunday from noon to 5 p.m. A closing reception will be held from 7 to 9 p.m. Nov. 10 .

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.