Investor Changes Mind, Says Name Was Not Forged

- Share via

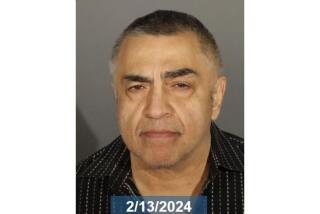

A Los Angeles real estate investor who told The Times that his signature had been forged on two deeds notarized by Ben Karmelich, president of Highland Federal Savings & Loan Assn., has changed his mind and signed an affidavit saying the signatures were genuine after all.

“Upon checking my records, there was absolutely no fraud or forgery,” Syed Mouzzam Ali said in the sworn statement. “I signed the two deeds.”

Ali’s affidavit, coupled with the recollections of a title officer who said she was present at the signing, indicate that Karmelich did not notarize two alleged forgeries, as The Times reported July 31. Karmelich has repeatedly denied ever notarizing forged signatures.

Based on Ali’s initial allegations, the California secretary of state’s office announced Aug. 3 that it had opened an investigation into the matter. In an interview Tuesday, James W. Randall, chief of the notary division, said he will drop that part of the investigation dealing with the notarization of a forgery.

However, he said investigators will still ask to examine Karmelich’s notary journal because “on the face, it appears he may have violated the (state) law” that prohibits notaries public from notarizing any transaction in which they have a “direct financial or beneficial interest.”

“The thing we were concerned about most, of course, was the forgery,” Randall said. “But at this point, this case is still open. . . . Where’s there’s one violation, sometimes there are more.”

The two deeds Ali now says he signed were part of a single transaction in which he sold two downtown residential hotels to a company controlled by Joe Fitzpatrick, a regular Highland customer and stockholder who was later convicted of 24 slum code violations on three properties, including one of the two hotels he bought from Ali in this transaction. Fitzpatrick declared bankruptcy in 1986, and left the state last year.

In that transaction, Karmelich and his wife appeared as beneficiaries on a $550,000 note recorded simultaneously with the two deeds. The Times article quoted a state banking official who said Karmelich’s personal involvement raised questions as to whether Karmelich may have violated federal conflict-of-interest regulations. Public records show that the note was paid off a few months later.

Violations Denied

Karmelich declined to discuss his financial involvement in the property except to deny any violation of law or ethics. “Mr. Karmelich feels strongly that the only thing he’s guilty of is being an active businessman,” his attorney, Michael Berk, said in an interview.

When initially asked about his signature in June in a 30-minute tape-recorded interview with two Times reporters, Ali was adamant that he had not signed the documents. He repeatedly described the signature on the two documents as “forged.”

He pointed out that the signature on both deeds was spelled out letter by letter. His own signature, he stressed, is an unusual combination of Arabic and English script. To prove his point, he emptied his wallet to show identification cards with his true signature, and demonstrated his signature for reporters. A longtime business associate of Ali’s confirmed he had never seen Ali sign a signature such as the one on the deed.

When it was pointed out to Ali in that interview that Karmelich had notarized the signature, he said: “I’m sorry, this is not mine. . . . (someone) forged it.”

Asked now why he had changed his mind, he said he had remembered that a title officer involved in the transaction had requested him not to use his normal signature, but to print his name instead.

“That must have been the only time I ever signed my name that way,” he said. “I signed those documents, but that is not my signature.”

In his affidavit, Ali says he met Karmelich, Fitzpatrick, and a title officer at what was then called the American Title Co. in Glendale at 6:30 a.m. on May 27, 1983. They met at that early hour, he said, because there was no escrow in the transaction and that he and Fitzpatrick, who had had prior dealings, did not trust each other. All sides, he said, wanted the sale to get “priority” recording at 8 a.m. at the Los Angeles County Recorder’s office. He did not explain why there was no escrow.

Timing Is Important

Title companies, which insure clear title to new buyers, generally insist on 8 a.m. “priority” recording to make certain no additional liens are recorded against a property between the time documents are signed and the time they are recorded.

Ali said the parties involved waited at the title office until the documents had been recorded. He said he then received a cashier’s check for $550,000 for the two properties, and went with Fitzpatrick to the bank to cash it.

Although Ali did not recall the name of the title officer, The Times reached Linda Blood, then branch manager of the company, who said in an interview that she was present at the meeting and recalled it in detail because it was the only such early morning transaction she had ever been involved in.

“It was all legitimate, but I had gotten legal advice beforehand because. . . . I had to determine it was a kosher thing to do,” she said. “They wanted to do it without an escrow . . . so money could pass hands upon confirmation and nobody could cheat anybody.”

She said Ali signed the documents, Karmelich notarized the deal, and checks were exchanged. She said she did not know Karmelich had any financial interest in the transaction.

Still unclear, however, is why Ali signed his name the way he did.

“I would never tell anyone to print their name,” Blood said. “That just doesn’t make sense. I also want signatures because you’re signing a legal document, just the way a bank officer would.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.