From $10 a Week to Station Owner : Radio Entrepreneur Sets High Standard

- Share via

GLOBE, Ariz. — When Willard Shoecraft first hit the airwaves, radio was most people’s major source of news and entertainment.

“Radio was a great and wonderful thing,” says Shoecraft, who is back at the helm of a station he founded, massaging listeners daily with his gentle yet authoritative and mellifluous voice, a throwback to an era when radio was king.

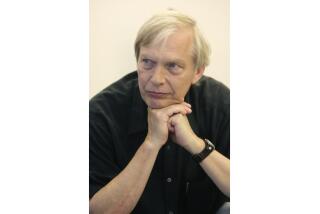

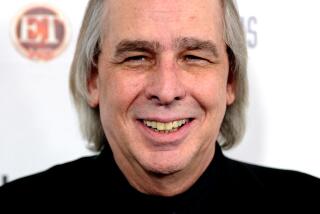

At 68, white-haired and mustachioed, Shoecraft is an engaging entrepreneur, raconteur, on-air pro and civic-minded world traveler.

He is also an example for others, though he insists on minimizing that.

When Shoecraft started June 1, 1939, just out of Phoenix Union High School, changing records at KGLU in Safford, he worked 70 hours a week, including the 6 a.m. sign-on to 12:15 a.m. sign-off on alternating Sundays as record master of ceremonies, “whatever that is.” The pay was $10 a week.

“It was the prime entertainment in those days, and it probably was fed a lot by the Depression,” Shoecraft says. “If you could get enough to buy a radio, this was your family entertainment, and it was free.”

Standard fare included Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and the “Kraft Music Hall,” the “Firestone Hour,” Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra.

“The best entertainment in the whole world, comedy and music and, it really meant more. To my way of thinking, it’s still just as magnetic if it’s done right. Of course, the competition now is fierce.”

Shoecraft, self-taught, has met that competition with his own brand of “little-town radio” a comfortable mix of talk, information, music and general help, plus a large dose of local news. “If it’s news in Globe, we’ve got it.”

The philosophy is simple: interact with listeners.

Here’s the formula:

- A morning “Open Line” call-in show.

- “The Money Tree,” offering $20 or more to callers who correctly answer five true-false questions, like whether President Truman sold his memoir rights in 1953 to the Saturday Evening Post (he didn’t; they went to Life magazine).

- “Trading Post,” a daily swap shop.

- Requests for work, clothing or other help for local needy citizens.

Then there are Larry King, California Angels’ baseball and other sports.

Shoecraft has lived in Globe since 1943. In 1958, he went on the air with his own station, KIKO-AM, originally broadcasting from the lobby of the Copper Hills Hotel. Eventually, he struck a deal with Inspiration Copper Co. to build a mobile-home park, and moved KIKO into one. He built stations in Safford and Winslow and sold them, then in 1979 established KIKO-FM, with the highest FM signal possible, carrying 80 miles into Phoenix.

Over the years, he has made the most of turning bad luck into good fortune.

For instance, there was the time a hunter shot a telephone line, jumbling signals so a conversation between two women was broadcast over KIKO. Shoecraft faced a threat of being sued until he became friends with one of the women and her husband. And the woman’s sister, Billie, whom he married.

Shoecraft played piano in a bar, served on the City Council and as vice mayor, and once ran for the state Senate. “I was soundly beaten,” he says.

He served on the hospital and industrial development boards and was active in scouting. He and Billie, who died in 1976, raised three sons: an accountant-developer and noted balloonist, an attorney and a school administrator.

He subsequently married Billie’s nurse, Ruth.

Now, Shoecraft is running KIKO a second time. He sold the stations in 1987 for $1.75 million and bought back the AM station in June, 1988, for $125,000.

He provided “a vehicle for people to vent their feelings, sometimes in anger, sometimes in excitement, sometimes in joy, but whatever, the people have had an opportunity to be part of that radio station,” Miller says.

One other thing sets Willard Shoecraft a bit apart: Since an accident when he was 8, he has had no legs.

It’s one of the few things he doesn’t talk much about.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.