Reporter’s Notebook : Even a Violent Criminal Has an Introspective Side

- Share via

When Superior Court Judge Robert R. Fitzgerald sentenced James A. Melton six years ago to be executed for the robbery and murder of a Newport Beach man, he told the defendant it was too bad, because he liked him.

I remember being a little surprised. Covering Melton’s trial, I hadn’t found anything likable about him at all.

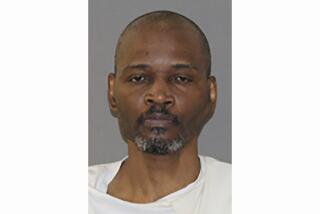

Melton, a large man, appeared menacing. He glared when spoken to. He never smiled or talked with his lawyer. He never watched the witnesses or even appeared to be listening to them.

During his death penalty hearing, he doodled on a piece of paper while two women who took the stand described in heart-wrenching detail how he had raped them. One rape occurred as the woman’s terrified young son watched.

During a short recess, I strained over the courtroom railing to see what Melton had been doing: He was drawing airplanes.

In many years of court reporting, I had never seen a killer so callous, so bored with the proceedings. He did not testify, even at his death penalty hearing. Even participation in his own trial appeared to be too much of an effort.

But that was six years ago.

Since doing interviews with Death Row inmates, I have come to know James Melton better. And now, as the judge who sentenced him, I see another side of him.

Melton, 37, now says that he had been given such heavy doses of prescription drugs at Orange County Jail that he was barely aware that a trial was going on. If he did not look at the witnesses, he says now, it was because he had no idea who was on the stand.

The outlook for a successful appeal for Melton is rather grim. The state Supreme Court turned down his first appeal earlier this year. Melton’s appellate attorney, Robert F. Kane of San Francisco, is genuinely convinced that Melton was impaired by a drugged condition and that kept him from getting a fair trial.

I believe Kane is a conscientious lawyer, but I have no idea whether Melton was drugged. I can only say that it’s surprising that the James Melton I have interviewed at San Quentin is the same person his jurors saw. He’s an interesting man, introspective, who searches for answers to why he became so violent. Melton at the trial was dull, mean-spirited, inhuman.

Kane recently asked me whether I would write a declaration about my observations of Melton during the trial. Kane had hoped that it would help support the appeal argument that Melton had been drugged.

This was out of the question, of course. Reporters are not supposed to be involved in their stories. But the request bothered me: Would I even want to help?

Melton acknowledges that he has a terrible criminal past but claims he is innocent of this murder. Do I believe him? No.

Melton and another inmate had been planning this robbery while he was in prison for a previous crime. Melton was found with the victim’s car and possessions.

With such overwhelming evidence, and with Melton’s incredible history of rapes, robberies and assaults, the trial results, including the death verdict, were inevitable.

But a nagging question remains: Did Melton really give his jurors any choice at all in deciding between death and life without parole? No. Melton, for whatever reasons, acted like his own worst enemy.

Melton’s first execution date, set for last month, was routinely postoned while his appeals continue.

Melton called me from San Quentin State Prison just before then. “You know my execution will be put off, and my lawyer knows it. But all I know is I’m set to die,” Melton told me. “This thing is getting so close, I figure I better get more involved.”

If Melton ever is executed, I’m not sure what my reaction will be. I do know I will feel a sadness that he probably never fully understood the terror he created on this earth. But I’ll also wonder: If Melton really wanted to save himself, why did he wait six years to try?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.