PACK MAN : New Hall of Famer Wood Was Green Bay’s Lombardi on the Field

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Green Bay was something. It was far and small and cold. Sometimes you went up from Chicago or Milwaukee in a DC-3. Sometimes you stopped in Oshkosh. On a Saturday night in Green Bay the streets were empty--if you walked a block the wind would tell you why. The bars would be full. Everybody would be talking about the Packers.

The Pack.

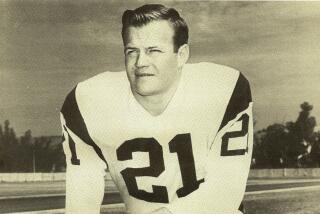

All those guys in this one little town, kind of giants of the Northland: Hornung and Taylor and Starr and Nitschke and Willie Davis and Herb Adderley and Forrest Gregg. They’re all in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. And Saturday--at last--they were joined by their free safety, Willie Wood. Willie Wood--alone--could bring down Jim Brown in the open field.

Wood came from the District of Columbia, a free agent out of USC with a dream of playing pro football. In 1960 he landed at this outpost that Vince Lombardi ruled like a foreign legion. No rookie had time to reflect on where he was: Depending on the viewpoint, the quaintest football town in America, or surely the end of the earth. Lombardi all but squeezed the life out of each player with mental pressure and physical torment--and who around there was going to tell Lombardi (with his gap-toothed maniacal grin) to chill out?

(A Packer, sitting in his motel room on the eve of a game, looked out his window and saw Lombardi, walking patrol. “There’s a man,” he said with contempt, “who doesn’t have a friend in the world.” That’s what many Packers thought of Lombardi then, but not what they thought of him when they won all the big games, and not what they thought of him when he left Green Bay, and when he died, and certainly not now when they think of him.)

“If I’m here,” said Wood, and indeed Saturday he was in Canton, Ohio, to be enshrined, “Vince had to be the one who got me here.”

A player who had been of no concern to so many pro scouts, general managers and coaches, Wood was as obvious as a snowstorm to Lombardi. He was fast and a sure tackler; he could hit a runner at the ankles and put him on his head. He could steal a pass, return a punt, block a kick and pick up other defenders’ slack. He never missed a game.

As the free safety, he was as free as any player ever was in the Lombardi scheme of football. He was the one player Lombardi expected a surprise from, and usually got.

Lombardi didn’t give leeway. When Jerry Kramer and Fuzzy Thurston pulled out from their guard positions for a Hornung sweep, they followed a road map. When Starr threw deep to Dowler or McGee, it was to the spot that Lombardi had pinpointed during the week. When Willie Davis rolled over an offensive tackle and wrapped up a quarterback, it was on Lombardi’s command.

What Wood could do and Lombardi loved to see was the flow of play reversed, suddenly going the Packers’ way with Wood running back an intercepted pass. Tucking the ball under his arm, he put away the first Super Bowl with an interception and 50-yard return.

But what Lombardi liked most about Wood was his leadership. In the still stellar “Instant Replay: The Green Bay Diary of Jerry Kramer,” Kramer wrote: “Next to Lombardi, Wood scares his own teammates more than anybody else does. Wood even scares Ray Nitschke. ‘I hate to miss a tackle,’ Ray says, ‘ ‘cause if I do, I know I’m gonna get a dirty look from Willie. He’ll kill you with that look.’ ”

To understand how tough Nitschke was, reserve Steve Wright helped put it in perspective. Before Wright took an off-season job with the Everseal Industrial Glue Co., which needed a salesman up in the Wisconsin area, the job was offered to Nitschke, who didn’t want it. Wright used to fantasize about Nitschke as a glue salesman: “He’d throw down a hunk of glue in front of you and say, ‘You want some glue? Here. Buy it.’ ”

The late Henry Jordan was tough too. Wright never has gotten over the tackle from Virginia, his life or his death. “He had back trouble and he used to get all doubled up with cramps on hot days. They used to straighten him out by hanging him up on a door. I can still remember ol’ Henry just hanging up there.”

If Wood was that tough and that good (eight Pro Bowls in 12 seasons, between 1960 and 1971), why did it take 13 times before he got enough writers’ votes to make it into the Hall? It’s been a hard wait. “People would ask me, ‘Willie Wood, why aren’t you in the Hall of Fame?’ I never had any comment on that. My wife was the spokesperson on that question. She wanted it for me.” She died, waiting.

Sheila Wood died a year and a half ago. “It was heart failure,” Wood said. “It was unexpected.”

Bad enough that Wood, a Washington businessman, has yet to be named to any coaching job or meaningful management position in the National Football League. But that didn’t stop him from becoming pro football’s first black head coach--in the World Football League and later in the Canadian Football League. Now he’s been out of the game since 1982.

He waited, Sheila waited.

Their three children were there for Saturday’s induction ceremony. So was his mother. “And half of D.C.,” he said. And Fuzzy and the gang: Thurston, Max McGee, Davis, Dave Robinson, Ron Kostelnik, Kramer, Paul Hornung, Adderley. . . .

The Packers always moved together. On Saturday mornings under Lombardi they’d take a train down from Green Bay to play “home” games in Milwaukee. Like an army slowly closing on the front, they rolled silently through the dairy land.

Before the war, however, was the fun. (They had it backward, but not by choice; it was off to Green Bay right after the game.)

“The first time I was out with the veterans,” Wright recalled, “was in Milwaukee. I thought I was really big time. I went downtown and bought a Stetson hat and that night I found a girl in town, picked her up and went over to a place.

“It had a back room, and all the Packers were there: Hornung, Jerry Kramer, Jim Taylor, Ron Kramer, Dan Curry, Max McGee, Fuzzy Thurston, the whole crowd. I walked back there with my date, and that was the last time I saw either the hat or her.”

Here they were again, all coming to Canton, to celebrate once more. For Willie Wood.

“Canton,” Wood said, “will never be the same.”

A lot of it now is just talk.

Of Vince.

Of the coldest day, of the deepest mud, of the heaviest rains, of the driving snows and of the clearings after the storms, the sunshine of their youth.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.