Scientist Says the Fate of Earth Depends on Whether Its People Mend Their Ways

- Share via

About 65 million years ago, a cataclysmic planetary event--probably a huge asteroid slamming into Earth and raising a smothering cloud of dust--wiped out the dinosaurs. You can see the evidence in the Earth’s crust, geologists say. A telltale layer of rock, formed just as the dinosaurs were disappearing at the end of the Cretaceous period, is salted with iridium, an element usually associated with asteroids.

Inventor-engineer Paul MacCready argues that the Earth could be, right now, in the midst of another cataclysmic event. This time, he says, the collision may be between the planet and its dominant inhabitant: man.

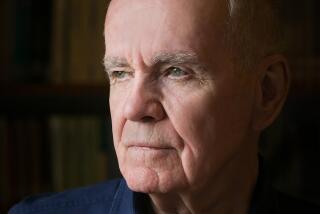

A slim, unsmiling man, MacCready was the brains behind, among other things, a human-powered aircraft that flew across the English Channel in 1979, and a teardrop-shaped car that scooted across Australia in 1987 fueled only by solar power. The Pasadena resident recently presided over a 10th-anniversary celebration of the cross-channel flight of the Gossamer Albatross.

Picture some intergalactic traveler digging into the Earth half a million years from now, says MacCready. The future space traveler, he says, may find all the signs of 20th-Century man’s profligacy right there, packed into a 200-year geologic layer “as distinct as the one 65 million years ago, when the dinosaurs were delivered the coup de grace. “

Species Disappeared

A grim prospect, concedes MacCready, president of a Monrovia environmental services firm, but consider what is happening to the planet. “All of the fossil fuel is being sucked out of the Earth and put into the atmosphere,” he said. “A huge number of species have disappeared. Man has overrun the Earth.”

All of which somehow relates to MacCready’s life work. Between the whimsical inventions he and his associates have masterminded, the “wind farms” his firm has plunked down in Southern California and MacCready’s systematic efforts to get people to think, there is a sense of mission.

MacCready is not given to self-importance. “I only spend about 15% of my time saving the world,” he said recently at the Athenaeum, Caltech’s faculty dining room.

But most of his time is devoted to learning to live in, as MacCready describes it, “an era of limits.”

Take the Gossamer Albatross, the 70-pound flying machine whose human-powered flight across the English Channel won MacCready a $200,000 prize. The contraption, looking like a huge plastic bag suspended from a 96-foot stretch of transparent wings, did not usher in an era of human-powered flight. But the cross-channel flight--with pilot-cyclist Bryan Allen pedaling 23 miles through the air--was a revolutionary achievement nevertheless, said MacCready.

Challenge in England

“In the United States, if you want to make a new vehicle, you use a better, more powerful engine,” he said. “That’s what I’ve grown up with. But suddenly a guy in England threw out a challenge: Fly on 1/4-horsepower.”

The whole idea was “sort of a new thing for civilization,” he said. “The new concept was: what can you do with less?”

Born in New Haven, Conn., the son of a doctor, MacCready has been intrigued by flight since he was a boy. “I found that model airplanes were a delightful hobby,” he said. “Looking back, I realize it was a good substitute for always being the smallest kid in the class with no coordination.”

The hobby was a great way to get started in aeronautics. “It’s a hands-on activity,” MacCready said. “You have to take responsibility for what you’re making. If I had been a football hero, I might just be an over-age jock today.”

MacCready joined the Navy in World War II as a flight trainer. After the war and graduation from Yale with a major in physics, he became engrossed in sailplaning. He won the U.S. National Soaring Championships three times and, in 1956, the international championship. He showed an early innovative streak too, inventing a device to help glider pilots select the optimum speed among thermal currents.

In the early 1950s, MacCready, by then the holder of a doctorate in aeronautics from Caltech, started his own firm to do research on cloud-seeding and atmospheric science. In 1971, he founded AeroVironment Inc., which manufactures pollution detection equipment, helps convert wind energy to electrical power, and comes up with all those fanciful air and land vehicles.

These have included, in addition to the Gossamer Albatross, the solar-powered Sunraycer, that traveled more than 1,800 miles between Darwin and Adelaide, Australia, in five days in 1987, beating its nearest competitor by two days. They also included the Solar Challenger, a solar-powered airplane that flew 161 miles from France to England, and a radio-controlled, wing-flapping replica of the long-extinct pterodactyl, the flying dinosaur.

Scientists engaged in more conventional technology have dismissed MacCready’s work as “fun and games.”

There is little practical value to his low-powered vehicles, MacCready concedes. But that is not the point.

“Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic in 1927 did not directly advance airplane design,” he said. “The plane was a lousy plane. It was unstable and you couldn’t see forward very well. You wouldn’t want to design another one like it. But it changed the world by being a catalyst for thinking about aviation.”

The Smithsonian Institution has recognized the symbolic value of the Gossamer Albatross, hanging it in a hall next to Lindbergh’s plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, and the flying machine the Wright brothers lofted at Kitty Hawk, N.C., in 1903.

MacCready sees most of man’s problems as relating to bad thinking. “We’re wiping out other species, and the attitude is: What good do some bugs amount to down in the middle of some rain forest?” he said. “The only concern seems to be whether there’s a direct, practical value to man. But we’re one species out of many, a newly arrived species.”