Forgive and Forget : Innocent Man Starts Over After 4 Years in Jail

- Share via

FRESNO — If you wonder how a man gets on with life after spending four years in jail, only to be set free because he was innocent, consider the story of Kevin Watkins.

Watkins was one of six co-defendants charged with the 1984 murder-for-hire of Carlo Troiani in Oceanside, a plan hatched by the victim’s wife. He spent four years in the San Diego County Jail at Vista awaiting his turn in the courtroom, was finally acquitted of all charges by a jury, and what did he do?

After settling down with his parents in Fresno, where he works for the family-owned asphalt and construction business, he returned to Vista to visit some of his old deputy sheriff friends, and he called the jail commander a couple of times to chew the fat and swap stories.

Watkins’ attitude is typical, those who know him say, of his four-year stay behind bars. This is, after all, a fellow who sent a Christmas card one year to Deputy Dist. Atty. Phil Walden, the very prosecutor who wanted him sentenced to death.

A Familiar Face at Vista Jail

Vista jail officials say they don’t know of any other inmate who has spent as much continuous time in their custody as did Watkins.

Let alone an innocent man.

But this isn’t a story about a man filled with anger, bitter about spending four years of his life in a black hole, talking of lawsuits or how the system burns even the innocent guy.

You bait him and you egg him on to get angry and finally Watkins allows that, well, he didn’t exactly like the prosecutor’s attitude toward him, but gee, Mr. Walden-- Mister Walden--had a job to do.

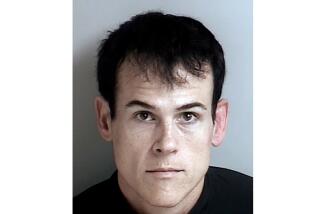

Meet Kevin Watkins, 23, returned to freedom after spending five birthdays behind bars for a crime he didn’t commit. You want him to get angry, and he won’t.

He’s polite. He folds his hands on the table when he speaks. He doesn’t smoke or drink or use vulgarity. For a good time, he rides his bicycle 100 miles or plays the guitar. He turns down invitations from his older sister and her husband to go out for an evening at the local Comedy Store, but he helps chaperon his younger brother’s fifth-grade classmates on a field trip to Sacramento.

The Well-Mannered Boy Next Door

Kevin Watkins is the kind of boy next door that grandmothers dream about, the handsome, well-mannered young man you hope your daughter marries.

Indeed, he’s not dating. He had one girlfriend, back from high school days, but that relationship crashed and burned after her parents learned that he was facing charges of first-degree murder.

“I don’t even know if they heard I wasn’t guilty,” Watkins said.

Actually, Watkins prefers the low profile, and for good reason. He spent four years of his life looking over his shoulder and learning not to trust too many people because, in jail, survival usually means keeping to yourself.

Now that he’s out, he’s not exactly ready to embrace the world like some therapy group.

That’s what may have gotten him in trouble from the get-go, Watkins said: Hanging out with some guys he didn’t know that much about. Now they’re all in prison for first-degree murder and he almost got caught in their wash.

The case centered on Laura Troiani, 24 at the time, who wanted her husband of five years, Marine Staff Sgt. Carlo Troiani, 37, killed so she could collect on his $96,000 life insurance policy and marry another Marine, Jeff Mizner.

Prosecutors allege that Laura Troiani hired five Marines to kill her husband: Mark Schulz, 20 at the time; Russell Harrison, 20; Russell E. Sanders, 19; Mizner, 21, and Watkins, 18.

Prosecutors claimed that the six discussed the killings several times and tried to kill Carlo Troiani three times before they succeeded. On one occasion, some of them tried to lure the man out of his apartment to pick up his wife, who supposedly was in a broken-down car in Carlsbad. But, when he left his apartment with another Marine, they backed off. Watkins wasn’t present.

Another time, some of them tried to bomb his car, but it didn’t go off. Watkins wasn’t present. Carlo Troiani supposedly laughed off the incident as a practical joke by the guys on base. Boys will be boys.

On the evening of Aug. 9, 1984, Schulz and Watkins went to Troiani’s apartment and Watkins was to stab him with a knife. But Watkins never took the knife out of his belt.

Several hours later, in the early morning of Aug. 10, Laura Troiani drove Schulz and Harrison to North River Road. The two Marines got out of the car and hid in the roadside rushes, and Sanders, at a nearby convenience store, telephoned Carlo Troiani and told him his wife needed help.

With Sanders at the store were Mizner, watching Laura Troiani’s two small children, and Watkins. When the sergeant pulled up, Laura Troiani tapped the brakes of her car twice as a signal, and Schulz fired his .357 magnum pistol, hitting the victim once.

He cried out in anguish and crawled beneath his wife’s car. Schulz walked up, pulled him out by his legs, stood over the sprawling Troiani, and shot him again in the back of the head, killing him.

Laura Troiani was arrested later that morning and finally came clean during interrogation. By the end of the day, the five Marines had been identified, and arrests came swiftly.

At the outset, prosecutors released Watkins and considered granting him immunity in exchange for his testimony against the others. Two weeks later, though, they re-arrested him and charged him with the others.

The prosecution was drawn out--over four years--because of myriad legal debates. Should all six be tried together, or at the same time but with six different juries, or separately? Was it proper to charge all six with the special circumstances of lying in wait and killing for financial gain? Should the trials be moved elsewhere? There was a host of other issues, involving evidence, jury selection and the like, that were hammered out before the first trial started.

Eventually, Laura Troiani was convicted by a jury of first-degree murder. The same jurors sentenced her to life in prison without possibility of parole. In a plea bargain, triggerman Schulz then pleaded guilty to first-degree murder with the promise that he wouldn’t be sentenced to death. Harrison, Sanders and Mizner followed suit, each pleading guilty to first-degree murder in exchange for sentences of 25 years to life in prison.

Only Watkins maintained his innocence and sought his day in front of a jury.

Pressured to Plead

He said he was pressured by others, including members of his own family, to plead guilty to a lesser crime, just to shorten his stay in prison. And at one time Watkins did offer to plead guilty to manslaughter because, by his fourth anniversary in jail, such a plea would have meant that he would have been released almost immediately given the time he already had served. He also wouldn’t have had to risk being convicted of a more serious charge of murder or conspiracy. The San Diego County district attorney’s office refused to accept a guilty plea to anything less than first-degree murder, though.

The prosecution’s case against Watkins was built somewhat on testimony by an acquaintance of the group who claimed Watkins was present during talk of the killing. The jury discounted much of what the woman testified to, however, saying she was less than totally credible.

Among the accusations against Watkins was that he sharpened a knife that was to be used in one of the murder attempts. But Marines sharpen knives all the time, and the incident didn’t damn Watkins.

True, Watkins and Schulz approached Troiani in his apartment. “We rode to his apartment on my motorcycle. I thought we were just going to see if he was there, so if he wasn’t, Laura could move out,” Watkins said. But, when they got there, Schulz gave Watkins a knife and told him to stab Troiani. If you don’t, Schulz said, I’ll kill you. He showed Watkins a gun.

‘Never Took My Hands Out’

“We went to the apartment--supposedly to pick up an Avon order--but I never took my hands out of my pocket,” Watkins said. “When we went back downstairs, Schulz was furious. He said he was going to kill me. I was scared to death.”

Watkins said he gave Schulz a ride back to a friend’s apartment and left after being assured by others that Schulz would cool off.

He rode to a nearby convenience store to buy gasoline, and the other four Marines and Laura Troiani drove up. Laura Troiani, Schulz and Harrison drove off, leaving Mizner with the two children and Sanders to make the phone call. “I stayed and talked to them,” Watkins said. “I thought they were going to try to move Laura out of her apartment again.”

The three returned about 20 minutes later, and the car had a flat tire--from a bullet hole, prosecutors would say later. Nothing was said at the time about the killing, Watkins said. He then helped ferry the Marines back to base on his motorcycle. Prosecutors said Watkins’ presence that night at the store, and the fact that he drove some of the Marines home, showed his involvement in the crime.

Arrested With Others

The next day Watkins and Schulz were together in Oceanside, and Schulz told him what happened. “All of a sudden all the pieces came together, and I realized that I was with them the night before,” Watkins said. The two rode back to base, and were promptly arrested by waiting Naval Intelligence Service officers outside his barracks.

“Everyone was telling me I’d be found guilty of something,” he said. “Even Brad (Patton, his court-appointed attorney) said there was a strong possibility I’d be found guilty of conspiracy.”

In jail, other inmates assumed he was guilty, too. That perception helped Watkins survive, he says now.

“The worst thing about jail is that no one has respect for anyone else,” he said. “You have to be on the offensive, and stand up for yourself. But at least not too many people challenged me because I was quiet, I kept to myself, and they knew I was in for murder. They weren’t sure if maybe I was nuts.”

Watkins didn’t disabuse the notion, and other inmates generally gave him breathing room.

Watkins spent his time reading, sleeping, sketching and working as a trusty, both in the jail library and in the kitchen, where for a year he worked 12-hour shifts as a baker.

“I sent away for all the junk mail I could get--catalogues, anything,” he said. His family called him every Sunday.

Model Inmate

Watkins was a model inmate.

Capt. Jim Marmack, the jail commander, said: “When he came in, I told him, ‘I don’t know how long you’re going to be in here, but think of yourself as joining the Navy instead of the Marine Corps, and you’re going to be on this ship for a while, and I’m your captain.’

“During his whole time here, I don’t think he had a single write-up, which is almost unbelievable when you consider how many deputies he had contact with over the years and the fact he didn’t antagonize any of them, not even with discourtesy.

“Some guys can seem squeaky clean and still cut off your ears. But, while he was in here, he earned our faith in him.”

Patton, his attorney, said it was “amazing” that Watkins didn’t crack or get in trouble during his tenure in jail, “given the element you’re exposed to in jail.”

Patton said he was impressed that, even when Watkins was finally freed, “he never talked of revenge or retribution.”

Watkins’ father and stepmother say they have seen subtle differences in their son because of his experience.

“He’s more reluctant to get involved with people,” Bill Watkins said. “It’s not that he’s afraid, but I don’t think he wants anything to do for a while with the world out there. He’s content to just kick back for a while and recover from all this. He spent a long time sitting alone in jail, and he learned to be patient.

“I compare him to a guy coming back home from Vietnam, having to relearn what society is, and changing from one set of rules to another.”

Watkins concedes that he grew weary during his last year in jail. His trial was moved to Ventura County because of extensive publicity in North San Diego County, and his jail experience in Ventura was sour.

At Watkins’ trial, Sanders testified that Watkins was kept in the dark about the plans to kill Carlo Troiani. When discussions were held plotting the murder, they usually occurred when everyone was riding in a car--while Watkins followed along on his motorcycle.

Watkins testified on his own behalf, saying it wasn’t until the night he and Schulz confronted Troiani that he realized they wanted him dead, and not simply out of the house so Laura Troiani could move out her belongings. By then, he said, he feared for his own life. He said he didn’t realize Schulz and the others were serious until the next day--when he was arrested.

Offered Plea Bargain

Watkins’ jury deliberated six days last June and couldn’t reach a conclusion, although most sided with Watkins’ innocence. Still, the fact that he wasn’t acquitted unnerved him, Watkins said. He offered the plea bargain to manslaughter, which the district attorney’s office refused because he would have been released from jail almost immediately, albeit with a felony record.

The district attorney’s office retried Watkins. The second jury acquitted him of all charges in October--first-degree murder, conspiracy and accessory after the fact.

“I was numb,” he said. “I just took a deep breath. I had been maintaining my composure for four years, and I was afraid if I showed my emotions then, I would lose control.”

After 50 months in jail, Watkins was returned one last time from courtroom to jail, where he had to again put on his jail clothes and wait three hours to be processed for freedom.

With a paper sack containing his few personal belongings, Watkins walked out the front door of the Ventura County Jail. He found himself in a strange city with maybe 30 dollars in his pocket and conscious, for the first time in years, of the sound of wind.

There were no family, no friends, no reporters. His own attorney had already left to catch a flight back home to Carlsbad.

A man walked up and offered to buy him a hamburger and a beer.

“He was one of the jurors,” Watkins said. “He said he hung around for the three hours because he wanted to meet me and see if he made the right decision. He said I seemed nice enough on the stand, and he wanted to see if he was right.”

“It’s unbelievable to me that anyone would have taken the time, and be that interested, to hang around and talk to me.”

The two ate at the airport while Watkins waited for his father to buy him a ticket home.

At home, his family was walking on eggshells for a time, Watkins said.

“There would be a discussion among the family about something, and then they’d say, ‘Oh, that happened while you were down there.’

“Well, I’m in no rush to find out all that I missed in four years. That’s lost time. I’ve asked myself, was there really a reason for this to happen to me? What was meant to be? But there’s nothing much you can do to change it.

“I wonder what I could have done during those four years. I could have gone to college. I could have won the lottery. If I could have at least had a guitar in jail, I’d be good at it by now.

“It doesn’t do any good to be mad at anyone, or to say I’m going to get even. To say I’m angry at Mr. Walden wouldn’t do me any good. It wouldn’t change anything.

“I won’t say I enjoyed it, because I didn’t, but I learned a lot.

“I learned not to judge people.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.