Explorer Has Done It All; Now He Heads Into Political Jungle

- Share via

LA JOLLA — He’s been dubbed the Indiana Jones of the Right, a man who has mounted expeditions to the far corners of the world, from the jungles of New Guinea to the hallways of Washington.

Jack Wheeler has lived more adventures than even Hollywood could dream up. He has climbed the Matterhorn and hunkered down with Amazon headhunters. At the age of 17, he shot a tiger known as the man-eater of Dalat.

Since then, Wheeler has retraced Hannibal’s route across the Alps aboard a team of elephants. He once swam the treacherous Dardanelles strait separating Europe from Asia. He also was the first man to parachute onto the frozen wasteland of the North Pole, a feat that landed him in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Of late, the 44-year-old La Jolla resident has tackled a different sort of challenge, becoming something of a force on the right-wing political scene in Washington. As founder of the Freedom Research Foundation, a small nonprofit group studying anti-Soviet insurgencies in the Third World, Wheeler is a leading proponent of aid for “freedom fighters” taking up arms across the globe.

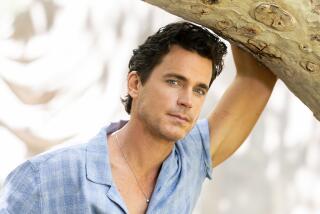

Some Administration insiders go so far as to credit the blue-eyed and boyish-looking explorer as a driving force behind the Reagan Doctrine, the de facto policy of assisting anti-communist troops in hot spots ranging from Nicaragua to Afghanistan.

“You can’t measure Jack by conventional standards,” said Rep. Jack Kemp (R-N.Y.). “The guy is influential in terms of giving people hope and planting seeds and his dogged pursuit of support for the freedom fighters. He has had an impact.”

Though not well known outside right-wing political circles, Wheeler has attracted a share of criticism from liberal factions. Some portray him as a bit player in the Iran-Contra scandal, as a man who knew many of the participants but steered clear of any criminal culpability.

“He was a real spark plug in that whole operation,” said Dan Sheehan, general counsel of the Christic Institute, a Washington-based public-interest law firm pushing a massive civil conspiracy lawsuit against several suspected principals in the Iran-Contra affair. “Jack Wheeler is, in a certain sense, one of the most appealing of those characters, in another sense one of the most dangerous because of that appeal.”

All that for a man who professes to “hate politics,” preferring a good 2,000-mile trip through Tibet to negotiating the Washington Beltway.

Jack Wheeler’s first love will always be adventure.

It also helps pay the bills. Aside from running his research foundation, the jocular adventurer operates Jack Wheeler Expeditions, a company that offers one-of-a-kind trips to the remote corners of the world for groups of eight to 12 people.

Want to witness the great migration of wild game animals across the plains of Africa? No problem. Wheeler will get you there. Eager to live with a group of wild bushmen in Botswana for two months? Jack can deliver.

Next year, Wheeler hopes to retrace the route of Marco Polo through the Far East using four-wheel-drive vehicles--if the Chinese government will give him permission. Another future expedition would follow the path Lewis and Clark took in their explorations of the Pacific Northwest, complete with canoes.

“One thing I have learned through the years is that the world is getting bigger,” Wheeler said while lounging in the second-floor office in his La Jolla home, which serves as the base for all his ventures. “The more I travel, the more I realize there’s more to see.”

Just a step inside the house, a relatively unassuming place on a quiet street overlooking the Pacific, reveals very quickly where Wheeler’s sentiments lie.

Massive, hand-hewn wooden war shields from New Guinea rest against a wall in the entryway. A huge trumpet horn from a Tibetan monastery hangs nearby. The bookshelves sag beneath the weight of countless volumes, among them works by Jules Verne, Voltaire, Victor Hugo and Thomas Jefferson.

In another room, a counter is loaded with the trinkets of a hundred trips--an Ecuadorean tribal headdress woven from toucan feathers, a monkey bone necklace, a belt buckle from a Soviet officer killed in Afghanistan, polar bear teeth, a Pygmy bow and arrow.

Nearby sit several pieces of skull bone that Wheeler says he picked off a battlefield where Genghis Khan fought. Right next to a framed picture of a smiling President Reagan standing with Wheeler and his wife, a La Jolla beauty consultant named Rebel Holiday, is a shrunken head encased in a glass box.

A simple philosophy has guided Wheeler on his adventures.

“The age of the universe is something like 60 billion years, but in all that time there is only one moment for each of us,” he said. “That moment is ours alone. And every individual has the capacity to make their life something special, especially in America.”

For Wheeler, the wanderlust started during his youth in Los Angeles. At age 14, he read a book by Richard Halliburton, an American explorer during the 1920s and ‘30s, that featured a picture taken from atop the Matterhorn.

Filled with teen-age zeal, the young man trooped down the hallway to tell his father, popular ‘50s late-night television personality Jackson Wheeler of KTTV in Los Angeles, that he wanted to follow in Halliburton’s footsteps.

The elder Wheeler took his son seriously. After all, young Jack was a precocious lad. Wheeler’s mother, Thelma, recalls that at the age of 2, Jack would determinedly surmount a five-foot barbed wire fence in the family’s back yard. At 12, he was invited to the White House to visit President Dwight D. Eisenhower for being the youngest Eagle Scout ever.

“He was adventurous even as a child,” said Thelma Wheeler, a widow now living in Las Vegas. “I certainly wouldn’t have allowed him to go on all those wild adventures; I’m too much of a worrier. But his father had great confidence in him, and when he realized Jack was sincere about this, he let him do it.”

The family was already planning a trip to Europe, so the boy got his chance to attempt the Matterhorn soon enough. With hardly a glitch, he followed a Swiss guide up the snowcapped slopes to the summit. At the top, his father shot a home movie from a private plane he had rented.

It didn’t stop there. Spurred on by the writings of Halliburton, Wheeler at 16 wrote an American doctor researching the medicines of Amazon tribes. The doctor invited him down for a visit, and Wheeler ended up spending several weeks living with a clan of headhunters.

The tribe virtually adopted Wheeler, initiating him by requiring the teen-ager to make his way through the system of lethal traps that each clan sets up on the periphery of its encampment.

“I almost got greased,” Wheeler recalls. “I tripped off one of these things with a big stake that comes flying up at you--whomp! It was like something right out of the movies.”

Next came a whirlwind trip to Greece, where Wheeler swam the frigid Dardanelles just after midnight in an attempt to duplicate the feat of Leander, the Greek mythological hero. With a Life magazine photographer and writer watching his every move, Wheeler made it to within 200 feet of his goal before the crew of the guide boat pulled him from the water for fear he’d dash himself on the rocks.

Jack then busied himself getting a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from UCLA and later went on to earn a Ph.D. in philosophy from USC. But the adventures didn’t stop. In 1961, he trekked to Vietnam, visiting some of the aboriginal tribes there and spending just enough time to bag a tiger that had been terrorizing a village near Dalat, in the country’s central highlands.

The journey sparked a business enterprise. In 1963, with the war just smoldering, Wheeler, still a teen-ager, and his father started a cinnamon exporting business in Vietnam, with Jack shuttling between college and Saigon to help run it. By 1967, however, the business was abandoned in the face of the escalating war.

Meanwhile, on a trip to New Guinea, Wheeler made what he says was the first contact by westerners with a tribe of cannibals.

He got along great with the natives and complains today that Hollywood has given the Western world a distorted view of the grisly practice. Typically, he said, the friends of a man who dies trade a pig for his body, which they drag off into the jungle to cook and eat so “the man will continue to live in the bodies of his friends.”

After getting his doctoral degree in the mid-’70s, Wheeler published a book of his travels, a volume of tales and how-to information called “The Adventurer’s Guide.” He also decided that he wanted “to live my philosophy rather than teach it” and started his expedition company.

With paying customers in tow, Wheeler’s travels continued: the Himalayas, the North Pole, Africa, South American jungles. He also became something of a TV personality, appearing on several occasions on Merv Griffin’s talk show, as well as with Johnny Carson and Tom Snyder. He even appeared in a Dewar’s scotch magazine ad, standing atop the North Pole.

By 1982, Wheeler had begun to branch out into a different realm: politics. As a young man fresh from college, he’d had a taste of it when he served as state chairman of Youth for Reagan during the 1966 gubernatorial campaign. He had burned out early but now felt a need to be a participant again.

While talking one day with longtime friend Dana Rohrabacher, then a Reagan speech writer, Wheeler was staring at a world map when he realized that the vast Soviet empire was being challenged on several fronts by anti-communist insurgents. He decided to make a trip to the front lines.

In all, he visited 14 countries, among them Mozambique, Angola, Nicaragua and Afghanistan.

When Wheeler returned to Washington from his five-month tour late in 1983, Rohrabacher made sure all the right doors were opened to him. The adventurer briefed numerous Administration officials, presenting a compelling slide show along with his talk, Rohrabacher recalls.

Out of those discussions emerged the Reagan Doctrine.

“If you’re looking for the genesis of the Reagan Doctrine, that’s it. It grew from there,” said Rohrabacher, who is now running for a congressional seat in Long Beach. “Jack was definitely the spark that lit the flame.”

Wheeler formed the Freedom Research Foundation and, under that flag, has continued to periodically visit the various battle fronts to keep abreast of the action.

Although he has posed with weapons beside anti-communist troops and admits to being friendly with Bob Brown, publisher of Soldier of Fortune magazine, Wheeler says he has never taken up arms for a cause. Moreover, he firmly rebuffs any suggestion that he is involved with the CIA or actually supplying weapons to insurgents.

“It would be pretentious for me to even offer to fight for them,” he said. “Besides, arms sales is a legal thicket--and I steer clear of legal thickets.”

Wheeler’s foundation, which is supported by private donations and maintains a mailing list of nearly 3,000 supporters, also publishes a monthly newsletter, “Freedom Fighter,” and is compiling a data base on anti-Soviet efforts.

In his treks through the Byzantine jungles of Washington, Wheeler has rubbed elbows with all the conservative standard-bearers.

He calls Lt. Col. Oliver North, the deposed National Security Council aide who is soon to stand trial for his role in the Iran-Contra affair, a close friend. Jeane Kirkpatrick, former United Nations envoy for the Reagan White House, and the late CIA director, William Casey, heard his reports from the front lines. Wheeler has also testified before congressional committees half a dozen times on the efforts of anti-Soviet guerrillas.

The Christic Foundation’s Sheehan suggests that Wheeler was “a second-string player” in the insurgent network “only by dint of his superior intellect.” Wheeler was savvy enough to stay “just this side of playing a role in overt acts,” Sheehan contends.

Sheehan recalls how Wheeler shared the podium with Contra leader Adolfo Calero and retired Army Maj. Gen. John Singlaub, a figure in the Iran-Contra affair, at a Washington conference of rebel supporters in 1985.

“It was a very scary group,” Sheehan said. “I was kind of taken aback by the whole thing. He was jumping up and down and advocating support for private armies in some six different theaters. . . . It was a fine line between free-speech advocacy and direct solicitation for people to engage in violations of the Neutrality Act.”

Among his right-wing brethren, however, Wheeler is held in lofty esteem.

Rep. Charlie Wilson (R-Tex.), a leading proponent of U.S. support for the Afghan rebels, calls Wheeler “a real positive force” in the effort to help anti-Soviet rebels throughout the world.

“He knows as much as anyone without top-secret clearances, and he knows more than a lot of people I know with security clearances,” Wilson said. “Like anyone else, I wasn’t sure at first just how real Jack was, but I found out it’s all true.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.