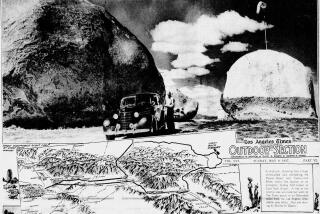

Assault on Australia’s Ayers Rock

- Share via

ULURU NATIONAL PARK, Australia — Our faces were as red as the rock we were climbing, but pesky black flies kept us from opening our mouths to gulp extra air. On the pretense of enjoying the view, we sat down to catch our breath.

We still gripped the thick metal chain that was our lifeline for an ascent that seemed straight up. Looking down the slippery mountainside, we recalled what a park ranger had said when we asked whether it was easy to climb Ayers Rock.

“There have been 18 deaths we know about,” he said. “Five falls and 13 heart attacks.”

That was hardly the kind of encouragement we needed to make an assault on the world’s biggest and best-known monolith.

But then the ranger added that one of the climbers who made it to the top was an 80-year-old woman. “There was even a month-old baby who got there on his dad’s back,” he said.

Why climb Ayers Rock? We didn’t even know you could scale that 1,142-foot-high sandstone bulge in the Australian outback until we were headed Down Under.

National Adventure

An Aussie seatmate on our transpacific flight remarked that climbing Ayers Rock was a popular adventure for his countrymen. “Sorta like you Yanks going down to the bottom of the Grand Canyon.”

A few days later we stood at the base of the immense 600-million-year-old rock, focal point for visitors to a barren desert area known as the Red Centre in the heart of the continent.

Australia’s aborigines consider the lone mountain sacred and call it Uluru. They also have a name for tourists, minga rama , which translates as crazy ants--just what everyone looks like when crawling up the face of the awesome monolith.

We arrived at sunrise with dozens of other would-be climbers, pausing only briefly to read a sign that warned that the climb was difficult and strenuous. People with heart conditions, serious asthmatic problems or a fear of heights are specifically advised not to attempt a trek to the top.

We felt reasonably fit, wore sneakers that are recommended for the slippery surface and carried a bottle of water. And we were there at the crack of dawn after being warned that the chance of heat exhaustion rises with the desert temperature, which can soar past 100 degrees in summer (November through March).

One Mile Per Hour

We were told that it was a two-mile round trip, accomplished leisurely in two hours. Looking up from the ground, the climbing route had no zigzags and appeared to go straight to the top. Our goal was the unseen cairn at the summit, where we could sign a visitors book to proclaim officially, “I climbed Ayers Rock!”

Gift shops 12 miles way at the Yulara Tourist Resort sell T-shirts with the same boast, as well as another version for anyone who cops out: “I Climbed Chicken Rock.”

The first 30 yards or so is an ankle-bending climb up smooth sandstone at a steep angle. It has some climbers aping their ancestors on all fours. Those who decide that this is no way to enjoy their vacation inch their way to an outcropping dubbed Chicken Rock, then retreat to the desert floor.

Huffing and puffing, we made it past Chicken Rock to the first of two sections of suspended chain.

They offer a necessary handhold for the most severe 60-degree angles of ascent. Unfortunately, the chain is attached to poles that reach a height only comfortable for midgets, so back pains were added to the throbbing muscles in our legs.

Bent over, hand over hand, we inched our way upward along the chain. Other climbers became obstacles as they collapsed momentarily along the route. And we got in their way while stopping to swat the irritating flies or wipe the sweat that was running into our eyes.

Onward and Upward

Our hearts thumped loudly, both from excitement and exhaustion, as we neared the top of the second length of chain. Then came groans instead of congratulations as we realized the chain had ended but the trail didn’t. A broken white line led over the rock’s undulating top to a higher point in the distance.

Although we had countless gullies and ridges to cross en route to the summit, the going seemed easier. Splotches of bright green surprised us; a closer look revealed it as algae, growing on pools of the infrequent rainwater trapped in the sandstone.

Best of all were the magnificent views of the endless desert and another landmark, the Olgas, a rounded rock formation of 36 domes erupting from the horizon. Also in the distance we saw Yulara and longed for a dip in the swimming pool.

Resort Complex

The $118-million resort opened in 1984 to accommodate visitors to this remote region. Its three hotels, campground, restaurants, shops and airport require a staff of 500, the fourth-largest population in Australia’s Northern Territory.

More than 220,000 travelers annually visit Uluru National Park, which encompasses Ayers Rock and the Olgas, and as many as 75% of them try to climb the rock. When we finally reached the summit to enter our names for posterity in the visitors book, signatures already entered that day were by Germans, Japanese, New Zealanders, Swedes and Americans.

Most others were by Australians, and their comments in the book showed the mood of celebration of everyone who makes it to the top. “Where’s the pub?” was one Aussie’s jubilant note.

The thought of an ice-cold beer made us eager to retrace our steps going down. Unlike the climbers, who were on the way up, we wore happy smiles.

For more information, contact Tourism Australia, 2121 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 200, Los Angeles 90067, telephone (213) 552-1988.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.