Judge Calls Latest Spy Case ‘Thin’ : Says Witness Affidavit Is Not Enough Proof for Indictment

- Share via

WASHINGTON — A federal magistrate advised the FBI Monday that it must add “a lot more meat” to its case against Randy Miles Jeffries, the stenographers’ messenger arrested Friday as an espionage suspect, if the government is to make its charges stick.

After hearing Jeffries’ lawyer argue that an FBI affidavit failed to show that Jeffries actually gave a Soviet agent highly classified transcripts filched from waste bags at the Acme Reporting Co., a stenographic firm, Magistrate Jean F. Dwyer recessed a preliminary hearing until today.

“I agree this is about as thin an affidavit as I have seen in recent years,” Dwyer said. “There is no way it will get by a preliminary hearing, unless by then there is a lot more meat.”

The magistrate said she would determine whether the government has shown probable cause to seek an indictment and decide whether to set bond for Jeffries after considering the government’s case at today’s session. Jeffries will be held in the meantime.

The affidavit, submitted by FBI Special Agent Michael Giglia at Monday’s brief proceeding, included new details relating to Jeffries’ alleged theft of transcripts taken during closed meetings of the House Armed Services Committee. They were leveled by an unnamed informant, described as a fellow worker at Acme, and were not included in the original affidavit made public at the time Jeffries was arrested in a downtown Washington motel.

Elevator Chat Noted

The new affidavit said the witness told FBI agents that on Dec. 14, Jeffries replaced him on his job of tearing up and discarding classified documents marked “secret” and “top secret.” On the elevator after work, the affidavit alleged, “Jeffries said that he had some of the documents which had not been torn up,” hidden in the building’s garage.

Jeffries then left the elevator and returned with about 200 pages hidden under his coat, the affidavit said. The witness described them as “the same ‘secret’ and ‘top secret’ documents that he and Jeffries had been ordered to tear up earlier in the day.”

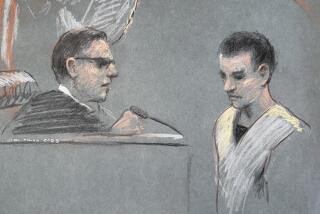

The slim, 26-year-old defendant, wearing a gray and black argyle sweater, sat silently while his attorney, G. Allen Dale, asked that the government’s complaint be dismissed on the ground that there was inadequate documentation.

Dale maintained that the charges were sustained by “no more than an idle boast” uttered by his client, who was quoted in the affidavit as telling an FBI undercover agent “he had met with Soviet officials on two occasions and had delivered to them portions of documents” and had requested $5,000 “to deliver the complete package of three documents.”

Among observers at the hearing was Stephen Ross, counsel to the clerk of the House of Representatives, the office that sets procedures for hiring outside stenographers to supplement the regular House staff of 19 shorthand reporters. Of these, 11 are regularly detailed to transcribe hearing records while the others are assigned to cover House floor debate and are available for duty at hearings when the House is not in session.

Work Under Contract

Ross estimated that there are perhaps a dozen days a year when the House’s own 19 stenographers are unable to cover all hearings. At these times, committees make use of about a dozen private firms that have won contracts through competitive bidding.

“We want to move, to the extent we can, to in-house reporters, especially for hearings where security is involved,” Ross told an impromptu news conference.

Ross said that the Defense Department has a clearance procedure both for stenographers and for the facilities at which transcripts are prepared and for the personnel involved, including messengers. He said, however, that delays of “almost a year” have made the procedure cumbersome.

Dale Hartig, a spokesman for the Defense Investigative Service, said in an interview that the office has a policy of inspecting any installation where there is a security breach. He conceded that there had been delays in completing clearances in the past, but said the process had been speeded up. In September, he said, the average clearance took 117 days.

Another review of the case is being undertaken by the Information Security Oversight Office of the General Services Administration. Its director, Steven Garfinkel, said the inquiry will explore the question of Acme’s compliance with a government directive that contractors disposing of classified material must shred, burn or pulp classified material once it is discarded. He said he did not know whether Acme officials had received the directive, which was circulated last year.

11th Spy Case This Year

Meanwhile, in a reflection of mounting congressional concern over the number of espionage cases, which reached 11 this year with Jeffries’ arrest, the Senate Intelligence Committee proposed a general overhaul of the government’s methods of handling classified information.

In recommendations forwarded to the National Security Council, the committee suggested that the recent rash of security breaches stems from “attempting to protect too much and thereby stretching personnel and other security programs too thin.”

Like other critics before it, the committee found both that too much material is classified and that classified material is too widely distributed. To staunch leaks of defense secrets to reporters, it called for a change in “attitudes that foster disrespect for the rules of secrecy” and steps to strengthen the principle that secrets should be circulated only on a “need-to-know” basis.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.