ECHOES OF A VOICE DEPARTED

- Share via

In the vacant-eyed days before television, we listened to the radio even when we weren’t in cars. The disc jockey had not yet been identified as a species, but there was recorded country music at dawn, advertising Peruna and Kolorbak Shampoo, and Lowell Thomas was well nigh compulsory listening after supper.

And, too, for what seemed like years, in late-afternoon homework time there was a marvelous variety show, five days a week on NBC from Chicago, which was the capital of daytime radio.

It was called “Club Matinee” and it featured a full studio orchestra, a couple of singers, a stooge or two and a captive announcer (Garry Moore) and was presided over by Ransom Miles Sherman, whose voice, even more nasal than Fred Allen’s, will reverberate forever in the audio memories of those who heard it.

Sherman died earlier this week at the ripe age of 87, in Boulder City, Nev., where he had lived for several years, and the melancholy news set off a rush of memory.

His professional public persona was of the rather pompous know-it-all who in fact had vast wells of ignorance and misinformation and was always being confounded by simple facts.

As I thought about it in later years, it occurred to me that Sherman’s character could have been vice chairman to George Babbitt in the Zenith Goodfellows Club. Sherman made himself seem the prototypical Midwesterner.

“Club Matinee” was a lot of fun in an innocent, corny way. In some ways it was, I suppose, the radio equivalent of a comic strip, “Smokey Stover,” much admired in those days by early teen-agers in love with outrageous puns, foolish names and lowbrow aspects of comedy generally.

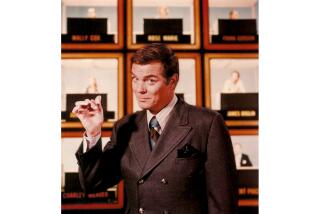

After the radio days, Sherman came to Hollywood and kept modestly busy as a supporting actor. He was the man in the severe glasses and the double-breasted suit, the very model of the assistant vice president in charge of complicating the lives of others.

Then television began and Sherman had an offer to go back to Chicago and try his hand at the new medium. The movie work was getting scarcer as the studios felt the competition of television. But his agent, Sherman told me later, urged him to stay.

“He said there was a part Dore Schary said only I could play. He was desperate to have me. Of course, it was only one day’s work. . . . I came back to Chicago.”

When I met him to do a magazine piece, “The Ransom Sherman Show” was a daily half-hour live TV variety show at 6 in the afternoon, with music by accordionist Art Van Damme (whom Sherman thoughtfully referred to as Art Van Darn) and his quintet, an announcer-accomplice--the young Hugh Downs, a personable pair of singers and Sherman himself, doing foolish things with film clips (I remember a shot of a beer truck turning a corner, with a voice-over that related to something else entirely).

John Crosby, who was then the country’s best-read television critic, was lavish in his praise of the show, as were other critics. It was, in fact, one of the glories of early television. Like the Sunday night “Garroway at Large” program, the Sherman show was the epitome of what seems in retrospect to be the Chicago style: an easy urbanity and an unobtrusive technical sheen plus a living immediacy that has been a prime casualty of tape.

The show did not last long enough--television was already departing Chicago for the coasts--but while it did, it was magical. Sherman was in fact an eager amateur magician, able to be funny when the tricks worked on camera, and funnier when they didn’t. At some point, I think, he actually ran a magic shop in Hollywood.

As sometimes happens, the private life of a man whose public life was to make people laugh was strewn with sadness, including the early death of a son. After the public years, I suspect Sherman was glad for privacy.

We had stayed in intermittent contact after our first meetings in 1950, and not long after I returned to Los Angeles in the mid-’60s we began to exchange birthday phone calls.

That cheerful, confident, crafty voice never lost its authority, but the kindness and good-heartedness that were always implicit beneath the flamboyant performances moved to the top, as it were. If the accent was Midwestern, so was the steadiness in the face of good times and bad, and so was the generosity of spirit.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.